BOOK REVIEW | The speculative practices shaping Indian cities

A Review of Llerena Guiu Searle's Landscapes of Accumulation: Real Estate and the Neoliberal Imagination in Contemporary India

By Meher Bhagia

In the early 2000s, a new narrative about economic growth in India began circulating among real estate investors. This narrative muddled stories of rising land prices with accounts of growth in GDP, incomes, the IT sector, and public infrastructure. Llerena Guiu Searle, an anthropologist, traces the circulation of these stories from business magazines to government publications and developers' presentations. The investment bank Goldman Sachs, for instance, played a part in re-branding India as one of the world's "emerging" economies, grouping it together with Brazil, Russia, and China (i.e. "the BRICs"), thus positioning India as a profitable investment destination. This collective narrative–the "India story"–was so ubiquitous that it became accepted common sense. After all, there was no statistical data to prove otherwise. In this insightful contribution, Searle provides ample examples of how such speculative knowledge creates concrete realities.

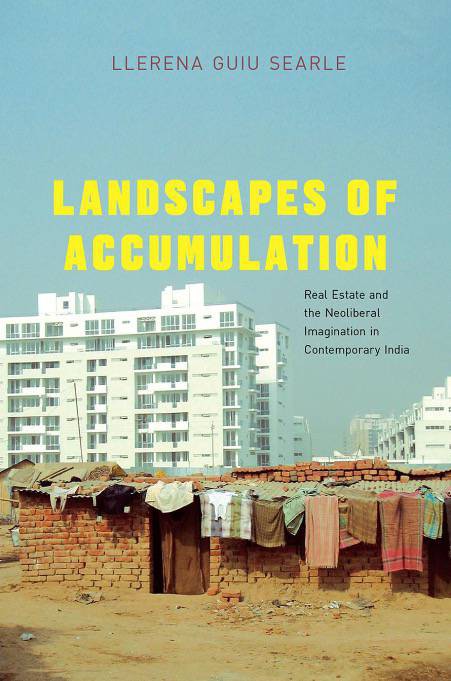

Landscapes of Accumulation explores the neoliberal capitalist processes through which buildings are produced in contemporary India. Specifically, it examines how agricultural and industrial lands are transformed into a resource by and for international financial capital in Gurgaon, a satellite city of New Delhi. Searle not only relates Marxist geographic theory to practise, but also reveals the limitation of David Harvey's argument regarding land markets as a basic coordinating device for the production of capitalist landscapes in explaining the Indian situation. She argues that capitalists do not merely respond to the price signals in the already established land markets for the allocation of land to uses, they actively create new markets. Searle's key idea is that capital does not unfold on its own; capitalists use their agency to circulate, invest and accumulate it. She seeks out the work that people are doing to forge routes of accumulation. Building on Harvey's theory of "accumulation by dispossession," she focuses on accumulation, an aspect that remains underexplored, while acknowledging that experiences of dispossession, such as violent resettlement of the urban poor through land acquisition policies, have been well documented by scholars.

Searle dedicated sixteen months to ethnographic fieldwork in India for this research. She engaged in participant observation with a European real estate fund ("EuroFund") and interviewed more than 140 people involved in the real estate industry including developers, architects, planners, fund managers, investors, brokers, bankers, journalists, and high-rise housing residents. Unlike most ethnographic research studies, this work is not a place-based account. The "ethnographic object" is the encounter, or communications, between foreign investors and their Indian intermediaries as they attempt to produce a global market for Indian land and buildings.

The book is divided into two main parts, each subdivided into four chapters. In Part I (Chapters 1-4), "Speculating on Indian Futures," Searle explores factors contributing to high demand for land by Indian capitalists and land profitability. She argues that high-rise buildings in India are speculative gambles based on forecasted social and economic changes, and not the actual changes. Many of her informants suggested to her that she should personally invest in real estate since "real estate is something that has to be appreciated" (p. 50). The unprecedented appreciation of land values in India was fuelled by such narratives that "conjure the possibility of profit." Anna Tsing calls this phenomenon "spectacular accumulation," when investors speculate on a product that may or may not exist, drawn by the appearance of success.

The stories soon translated predictions into prescriptions. Following the liberalisation of the real estate sector in 2002, and the opening up of foreign direct investment in Indian realty in 2005, foreign investors entered India's real estate market en masse, lured by the media and their stories of India's growth. Developers and fund managers offered prescriptions, such as the number of shopping malls and hotels needed in cities to "catch up" with the developed nations. The speculative nature of rising property prices and the possibility of a sudden crash was dismissed by almost everyone in the industry. Even as rumours circulated about falling prices and some investors exiting the market in 2007, developers and investors clung to the hope that the "genuine resident" would revive the market. The belief in the "India story" persisted, particularly the notion that the growth of the IT industry and multinational corporations in India would create more high-wage jobs and increase exposure to Western culture, in turn altering housing trends.

Searle also argues that spectacular accumulation is made possible by changing the social relations and practices in which land and buildings are embedded. Chapters 5 and 6 mainly explore investors' attempts to make the Indian real estate industry more "transparent." Drawing on James Scott's work on legibility, Searle explains that this "transparency project" is a tool of power that simplifies, standardises, and transforms people and practices. In the Indian context, multiple layers of contacts and local knowledge are required to construct buildings, due to the complex processes through which land parcels are consolidated, permits obtained, land uses changed and building plans approved. Foreign investors aiming to transform Indian land into an internationally legible and risk-free asset rely on local real estate developers to navigate the system, thereby integrating them into global capital flows.

In Chapters 7 and 8, the author traces the friction in the relationships between foreign investors and Indian developers. EuroFund's profit strategy revolved around creating superior-quality buildings. This "quality project" relied on positioning their buildings as "international" and themselves as "experts." For EuroFund, quality meant not just structural integrity but also a built environment conforming to the tastes of the global business elite. In contrast, Indian developers focus on land acquisition expertise over building construction quality. They prioritise minimising costs, maximising margins, and expediting project completion. This tension underscores the diverse capitalist practices shaping India's urban landscapes.

Searle concludes the book with an account of her experience returning to Gurgaon in 2014. Despite the city's drastic transformation, the landscape she observed did not align with the one envisioned by many in 2006. The global financial crisis of 2008 had created plot twists in the "India story." None of the urban projects had met their delivery deadlines, and the private developers involved were heavily indebted. However, despite this apparent failure, the value projects described in the book created conditions for new value projects. For instance, Blackstone, a private equity fund based in New York City, bought many devalued commercial buildings in India after the 2007-8 crash, amassing a portfolio of Indian assets larger than that of Delhi Land & Finance (DLF), a prominent local developer. Creating such routes of accumulation requires a lot of work; capital does not move on its own accord.

In Landscapes of Accumulation, the author reveals the work people are doing in producing and circulating capital. The reader will find themselves engrossed and amused by the anecdotes and stories interspersed throughout the book. Written in lucid English, the book is accessible to many. It will appeal to students and scholars in human geography, urban studies, urban planning, architecture, anthropology, and political science, and is indispensable for anyone seeking to understand neoliberal urbanisation in the contemporary Global South.

Edited by: Jesse Fox

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.

Comments