The promises of participatory budgeting

In a previous post, I was writing about participatory practices in urban development, particularly from the point of view of neighbourhood planning. A few days later, while attending the Central and Eastern Europe Civil Society Forum, I took part in a series of sessions which made me think further about the “civic enthusiasm” which seems to have appeared in countries where citizens have usually been absent from the public sphere. For me, a red line of the discussions was the need to channel such movements from their current reactive nature, to a more proactive one, which encourages participation in all phases of the planning process.

What other tools, apart from neighbourhood planning, have been tested and can work in Central and Eastern Europe as well? I was struck by the story of a participant. They had been struggling for a few years to introduce participatory budgeting as a practice in the city of Cluj Napoca, Romania, a process led by a few NGOs, only to realize when implementing it that citizens found it hard to formulate any concrete proposals. This made me think further whether participatory budgeting (PB) is indeed an effective tool and whether it can indeed be transferred from a Latin American context to a European one.

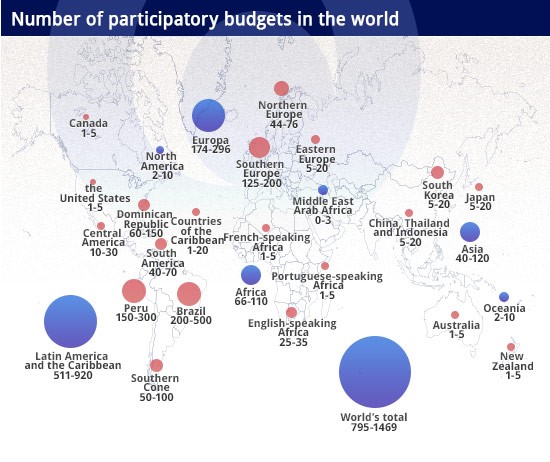

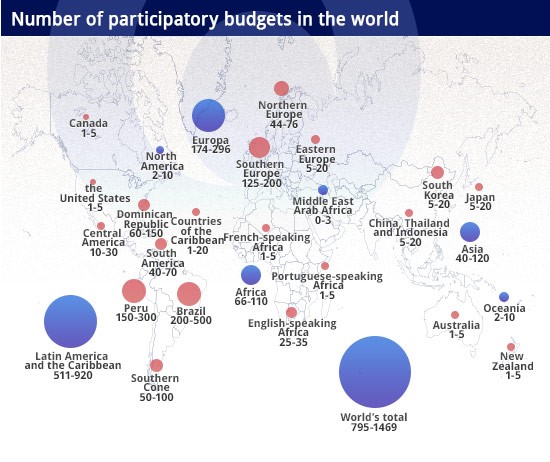

Number of PBs in the world, www.obserwatorfinansowy.pl, 2012

Number of PBs in the world, www.obserwatorfinansowy.pl, 2012

In essence, PB allows participation of non-elected citizens in the conception and allocation of public finances. Its birthplace, or better said, the best known and most successful experiment of local management based on participatory democracy is Porto Alegre, a 1.4 million inhabitants city in Brazil. What made Porto Alegre a best practice in participatory budgeting was not the scale of participation (in its early stages, it was in fact very low) but its success in engaging segments of the population which had usually been disengaged from planning. According to a World Bank report, sewer and water connections increased from 75% of total households in 1988 to 98% in 1997. The priority areas of PB in its first stages (1992-2005) included paving, basic sanitation and land use regulation (housing, relocation of families in slums), reflecting intra-urban disparities in access to services and utilities.

From Porto Alegre, PB spread to more than 600 cities in Latin America (between 618 and 1,130, according to this report) and further across the world, although in different forms which are not necessarily an accurate mirror of their Brazilian birthplace. Some academics (namely Yves Sintomer), however, have come up with criteria to help differentiate PB from other types of participation:

Top three PB winner projects in Paris, www.budgetparticipatif.fr

Top three PB winner projects in Paris, www.budgetparticipatif.fr

As for Cluj-Napoca, the Romanian city went through its pilot phase in 2013, when PB only focused on one neighborhood – Mănăștur, concentrating about one third of the city’s population – aiming to be spread to the scale of the whole city in 2014-2015. The initiative was focused on developing and testing a process which could be expanded and thus involved a high number of meetings, focus groups and surveys aiming to enable citizens to better formulate their demands. However, it is worth noting that the process was triggered essentially bottom-up by a number of non-governmental organizations beginning with 2012.

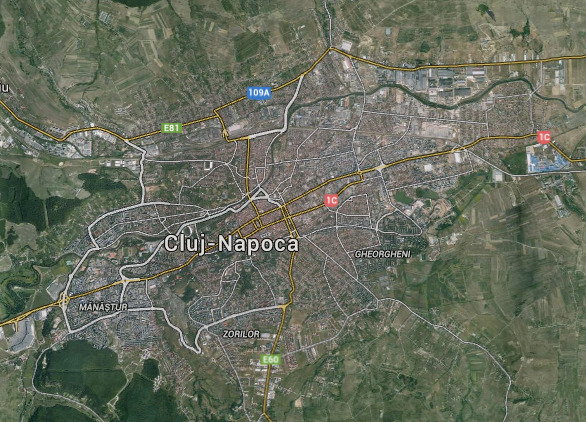

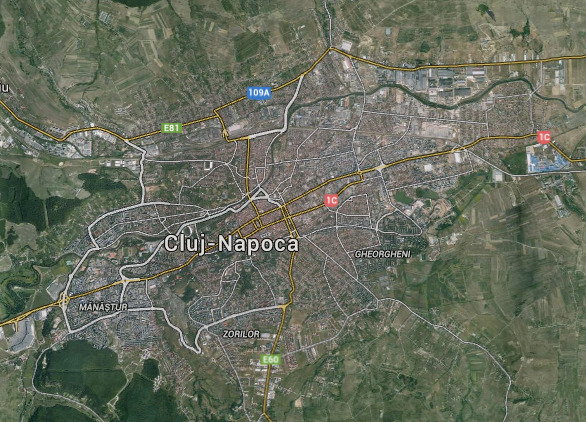

Map of Cluj-Napoca, Mănăștur neighbourhood South-West.

Map of Cluj-Napoca, Mănăștur neighbourhood South-West.

Although essentially different in their local and geographical contexts, the three examples above pose some interesting questions about the promises and challenges of participatory budgeting. Much like other types of instruments aiming for public engagement, PB raises the question of who gets engaged and who decides. This is a question worth to be posed both top-down (what tools a local authority uses to communicate its PB initiatives, how it informs its citizens of the „rules of the game”) and bottom-up (are citizens prepared to express their demands?). As the story about Cluj Napoca proved, the latter depends on building local capacity, and it is useful here to think of PB not only as an end, but as a means – an instrument for increasing transparency and a vehicle for citizens to practice (and get used to) participatory mechanisms. If one has never been involved or even tried to understand how a system works, how else could one bring a meaningful contribution?

We tend to create myths around best practices because they show us that it is possible to achieve meaningful results through innovative tools. But even if we take into account the successes in Porto Alegre, we cannot deny that after 2004 PB has been reduced in its scope (although not effectively abolished), following a series of political changes. Apart from proving that there is no “one size fits all” solution, this also points that in order to be sustainable, PB needs to be practiced, reinforced and supported in a sustained manner, if it is to be more than a showcase of successful investments at a particular moment in time.

What other tools, apart from neighbourhood planning, have been tested and can work in Central and Eastern Europe as well? I was struck by the story of a participant. They had been struggling for a few years to introduce participatory budgeting as a practice in the city of Cluj Napoca, Romania, a process led by a few NGOs, only to realize when implementing it that citizens found it hard to formulate any concrete proposals. This made me think further whether participatory budgeting (PB) is indeed an effective tool and whether it can indeed be transferred from a Latin American context to a European one.

Number of PBs in the world, www.obserwatorfinansowy.pl, 2012

Number of PBs in the world, www.obserwatorfinansowy.pl, 2012In essence, PB allows participation of non-elected citizens in the conception and allocation of public finances. Its birthplace, or better said, the best known and most successful experiment of local management based on participatory democracy is Porto Alegre, a 1.4 million inhabitants city in Brazil. What made Porto Alegre a best practice in participatory budgeting was not the scale of participation (in its early stages, it was in fact very low) but its success in engaging segments of the population which had usually been disengaged from planning. According to a World Bank report, sewer and water connections increased from 75% of total households in 1988 to 98% in 1997. The priority areas of PB in its first stages (1992-2005) included paving, basic sanitation and land use regulation (housing, relocation of families in slums), reflecting intra-urban disparities in access to services and utilities.

From Porto Alegre, PB spread to more than 600 cities in Latin America (between 618 and 1,130, according to this report) and further across the world, although in different forms which are not necessarily an accurate mirror of their Brazilian birthplace. Some academics (namely Yves Sintomer), however, have come up with criteria to help differentiate PB from other types of participation:

- the prerequisite of discussing the financial and/or budgetary dimension;

- the process has to take place at the city level or at that of a decentralized district;

- it must be a repeated process;

- it must include public deliberation;

- the local authority must be accountable for implementing the targets set through PB.

Top three PB winner projects in Paris, www.budgetparticipatif.fr

Top three PB winner projects in Paris, www.budgetparticipatif.frAs for Cluj-Napoca, the Romanian city went through its pilot phase in 2013, when PB only focused on one neighborhood – Mănăștur, concentrating about one third of the city’s population – aiming to be spread to the scale of the whole city in 2014-2015. The initiative was focused on developing and testing a process which could be expanded and thus involved a high number of meetings, focus groups and surveys aiming to enable citizens to better formulate their demands. However, it is worth noting that the process was triggered essentially bottom-up by a number of non-governmental organizations beginning with 2012.

Map of Cluj-Napoca, Mănăștur neighbourhood South-West.

Map of Cluj-Napoca, Mănăștur neighbourhood South-West.Although essentially different in their local and geographical contexts, the three examples above pose some interesting questions about the promises and challenges of participatory budgeting. Much like other types of instruments aiming for public engagement, PB raises the question of who gets engaged and who decides. This is a question worth to be posed both top-down (what tools a local authority uses to communicate its PB initiatives, how it informs its citizens of the „rules of the game”) and bottom-up (are citizens prepared to express their demands?). As the story about Cluj Napoca proved, the latter depends on building local capacity, and it is useful here to think of PB not only as an end, but as a means – an instrument for increasing transparency and a vehicle for citizens to practice (and get used to) participatory mechanisms. If one has never been involved or even tried to understand how a system works, how else could one bring a meaningful contribution?

We tend to create myths around best practices because they show us that it is possible to achieve meaningful results through innovative tools. But even if we take into account the successes in Porto Alegre, we cannot deny that after 2004 PB has been reduced in its scope (although not effectively abolished), following a series of political changes. Apart from proving that there is no “one size fits all” solution, this also points that in order to be sustainable, PB needs to be practiced, reinforced and supported in a sustained manner, if it is to be more than a showcase of successful investments at a particular moment in time.

Stay Informed

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.

Comments 1

[…] a quick and excellent state-of-the-art of participatory budgeting from 2014, do have a look this blog post by Irina […]