Toward Inclusive Cities 3.0 – aligning public participation with people

Is participatory planning about engaging everyone and making cities inclusive? Or about satisfying those who speak the loudest? These difficult questions affect public participation in cities throughout the world – for better or worse. After a brief discussion of what inclusiveness might be, this post explores how digital technologies for public participation can become more inclusive. It ends by considering the new wave in public participation innovation which merges both traditional and high-tech engagement.

The inclusive city – a promised land?

Wherever you live, there is likely to be room for improvement for making your city more inclusive. But what is an inclusive city? As relevant here, the Oxford Dictionaries defines “inclusive” as: “Not excluding any section of society or any party involved in something”. Inclusiveness is also linked to community. The sense of being part of a community, of belonging, is arguably a primordial human need and aspiration. “No man is an island, entire of itself. Every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main” wrote English poet John Donne in his Meditation XVII (four hundred years before Brexit, mind you).

The inclusive city, which should be pre-condition of planning, sadly remains an elusive mythical place. Inclusiveness is implicit in the notion of the “right to city” introduced by Henri Lefebvre in the late 1960s, which many authors have mobilised as a call for more equal opportunities and quality of life in the face of growing inequalities and disenfranchisement (e.g. David Harvey, Neil Brenner, Peter Marcuse).

The Occupy movement, a modern epitome of the right-to-the-city, began with Occupy Wall Street in September 2011 . Picture: wikimedia.

However, we need to clarify the notion of the “right to the city”, and especially explain exactly what kind of right(s) (moral, legal etc.) we are referring to. Transposed to public participation in planning, this implies specifying which “publics” are to be engaged, with the aim of leaving nobody out who may hold a stake. It also implies being clear about the purpose of public participation, and ultimately, the kind of rights on decision-making which citizens are entitled to hold in systems of representative democracy… Unfortunately, public engagement innovations in public participation can be said to have had only limited impact on policies. At the same time, the dynamics of local democracy are shifting, such as in the U.S., the UK, and France. In the UK, for instance, citizen-led Neighbourhood plans are mushrooming over the country. The future will tell if such Neighbourhood Plans truly help to reconfigure local democracy, and make cities more inclusive.

“Inclusive” also means: “(Of language) deliberately avoiding usages that could be seen as excluding a particular social group”. I interpret this last definition as: “speaking in a way which everyone understands and is not disparaging to anyone”. The lofty aim of collaborative planning is to invite everyone to the discussion table and agree to common goals that will benefit the common good. Such goal-oriented dialogue can help “re-enchant” local democracy. However, current public engagement practices often fall short of addressing social inequalities and making planning processes truly inclusive.

Public Engagement: 1.0 + 2.0 = 3.0

Digital technologies for public participation abound. Social media such as Facebook and Twitter, and the virtual environment Second Life have been used for engaging residents in urban planning, with varying successes, depending on context and technology. Easy-to-use online mapping software have engaged from hundreds to thousands in the planning of their neighbourhoods and cities (e.g. CommonPlace in the UK, coUrbanize in the US, Carticipe in France, Maptionnaire in Finland, Bästa Platsen in Sweden). Games such as Minecraft have also been used to engage youth throughout the world. A flurry of recent hybrid portals provide multiple functionalities (e.g. coUrbanize, MetroQuest, among many others). These allow simple consultation as well as more active forms of participation. Functionalities include learning about projects (content, timelines, updates), budget allocation, mapping development preferences, ranking development scenarios and planning priorities, voting for proposals, etc. Digital and physical technologies can also be cross-linked: an online map survey, consultation meeting or traditional collaborative workshop (e.g. design charrettes) may be advertised on Facebook or Twitter; and contributions to an online mapping survey may be shared to various social media or advertised via physical mail or early consultation meetings.

The trend is toward compatibility across platforms and devices. Anttiroiko (2012) uses the term “Planning 2.0” to describe confluence of Web 2.0 technologies in the work of planning-related professionals and means of engaging urban dwellers. The data produced through public engagement is increasingly useable in the work of planning and design professionals. For example, 3D city models produced by professionals and amateurs alike can be uploaded to online interactive 3D city environments for public participation (e.g. Google Earth applications, CityPlanner, Urban Circus, etc.). Also, in the age of the Internet of Things, Big Data is being harnessed alongside government Open Data to better understand people’s needs and behaviour. Big and Open Data also create opportunities for ordinary (though often technologically-savvy) urbanites to contribute new knowledge and proposals that can improve urban planning and city life, for example through civic hackathons. Big Data is also about making sense of urban residents’ use of social media, which is really more about data mining then public participation, and can raise issues of data privacy.

Overall, such digital technologies have the potential to reach more people and more diverse groups, and in more creative, participatory ways, than many other traditional methods such as consultation meetings and design charrettes.

Digital technologies display clear limitations, however. First, the worlds of technological innovation and planning do not always converge. Nonetheless, this professional gap is also the sign of ample room for fruitful cooperation between planners and developers. Second, engagement through technology often remains limited. Social media are typically used as one-way communication from planners to users. Online mapping surveys are typically carried out as innovative consultation exercises. Third, empirical comparisons of digital and physical technologies are largely missing however, making it hard to assess the relative value of either. Fourth, planners and decision-makers need to take the lead in improving the outcomes of public engagement. Last and most importantly, the digital divide (lacking access or the skills to use digital technologies) is the Public enemy No 1. of Public Engagement 2.0. Therefore, evidence so far suggests that the potential to “wikify” or “crowdsource” the inclusive city remains only a potential (Silva, 2013). Is technology failing to deliver on its promises of revolutionising urban governance?

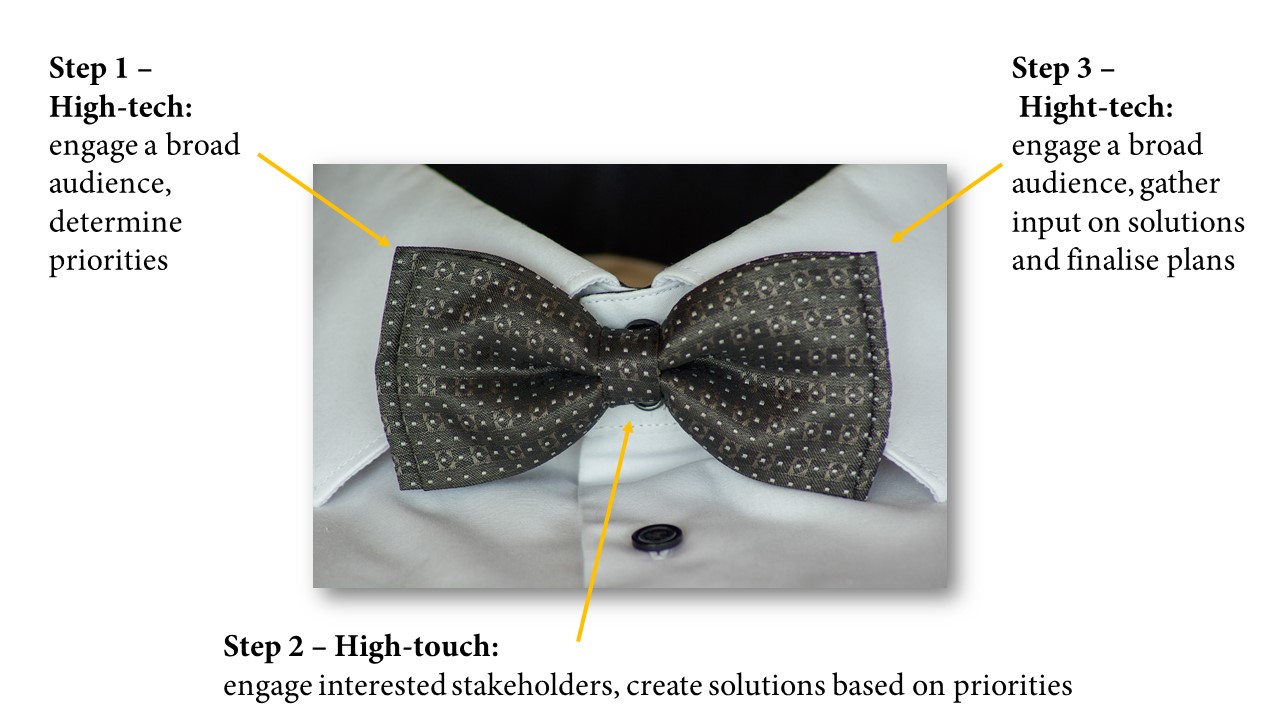

The middle-way may lie in combining traditional and high-tech technologies in smarter ways. Dave Biggs, Chief Engagement Officer at the public engagement software provider MetroQuest, summarises his advice to combine “high-touch” (i.e. closer contact with customers through face-to-face participation) and “high-tech” (i.e. reaching the masses with a mix of online tools). He does this with a bowtie.

Public Engagement 3.0: "It's all in the bowtie". Adapted from Biggs (2015). Picture: Pixabay / Jackmac34

The message: engage the masses early on so as to design better public consultation meetings and collaborative workshops, the outcome of which can be fed back online to select the best planning options. The benefits: deploying multiple technologies enables to reach different people in different ways, and generate synergetic effects in the process. The approach encapsulates both professional experience and the state-of-the-art in public engagement research, although it would also require thorough assessment.

Epilogue: The Death and Life of Inclusive Cities (version 3.0)

If the “inclusive city” is fraught with many obstacles and contradictions, can we expect technology to solve urban inequalities? Hardly. As Jones et al. (2015, p. 333) summarise succinctly: “ICT is not a magic bullet for enhancing resident engagement in planning any more than participatory approaches guarantee good outcomes”. In other words: The local governance revolution will not be digitised.

Henceforth the need to combine both traditional and digital means of engagement. Public Engagement 3.0 combined with proactive leadership from planners and local politicians could lead to the Inclusive City 3.0: a city that genuinely aims to be inclusive both virtually and physically.

References

Anttiroiko, A.-V. (2012). Urban Planning 2.0. International Journal of E-Planning Research, 1(1), 16-30. doi: 10.4018/ijepr.2012010103

Biggs, D. (2015). Public Engagement 3.0. The next generation of community engagement: blending high-tech and high-touch public involvement. Retrieved from http://metroquest.com/public-engagement-3-0/

Jones, P., Layard, A., Speed, C., & Lorne, C. (2015). MapLocal: Use of Smartphones for Crowdsourced Planning. Planning Practice & Research, 30(3), 322-336. doi: 10.1080/02697459.2015.1052940

Silva, C. N. (2013). Open source urban governance: crowdsourcing, neogeography, VGI and citizen science. In C. N. Silva (Ed.), Citizen e-participation in urban governance: Crowdsourcing and collaborative creativity (pp. 1-18): IGI Global.

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.

Comments 2

Good text! And plus, since ICT don't resolve inclusion related issues, why don't we step back and identify / name (new) forms of exclusion? Who are those people that cannot share (i.e. don't have resources for) public power today? And how could we prevent from failing again, again, and again the first main goal of participatory mechanisms: social inclusion?

Social inclusion can be a hot potato unfortunately. In the end I think everyone (politician, student, lawyer, baker, full-time mum, carpenter, athlete, artist) can contribute to more inclusive communities in small and big ways alike, by caring about what's happening in their community. I think it's a shared responsibility.