Civil society initiative for user-generated urban development processes: equal partners in post-industrial cities?

Introduction

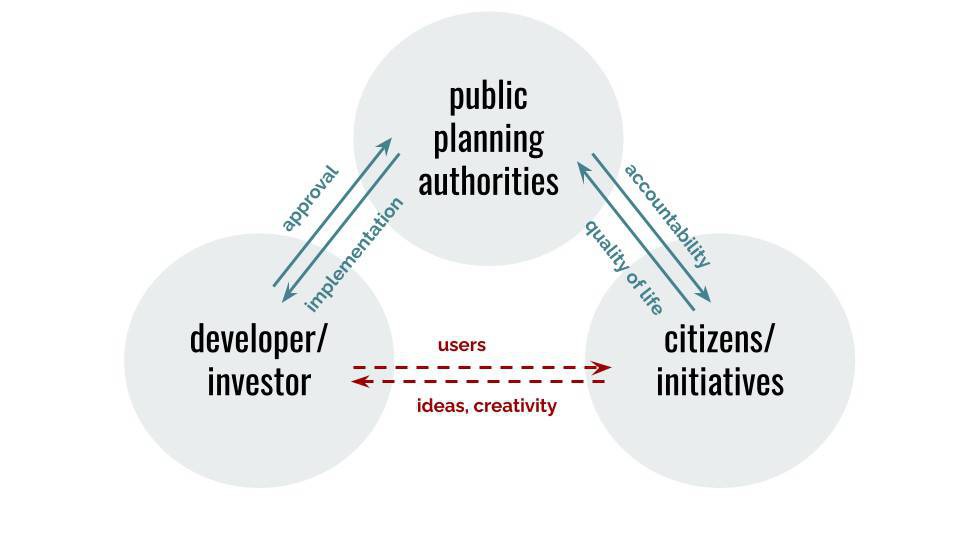

Cities in diverse contexts experience increasing civil society engagement through neighbourhood-scale, informal and citizen-based interventions. Local expertise provides civil society initiatives with a notable advantage over professional planners and offers the possibility to become place-makers – and ultimately urban planners – themselves (Healey 2015; Willinger 2014). In post-industrial urban settings with large-scale brownfield sites, urban development processes can succeed in the triangle of civil society, public administration and private property owners and developers. What happens if civil society organises itself when developing ideas for a vacant site are not yet in public debate? User-generated developments, where ideas and impetus start from the side of civil society, are central to a potentially new co-creative planning culture. Collaborative, self-organised projects, such as 'do-it-yourself urbanism', 'guerrilla urbanism' or 'temporary urbanism' cover a voluntary engagement for the benefit of the community. Recent efforts primarily focus on how public authorities can use local knowledge (through participatory approaches, facilitation, and cooperation) or make use of the potential of these small-scale user-guided projects.

We use the example of the initiative 'Neue Werk Union' (NWU, literally: new working union, but also new factory union, refers to the former name of the production site) in Dortmund (within the Ruhr region in Germany). We show dynamics and pitfalls emerging when a civil society initiative aims to open the planning process for a 44-hectare old industrial site in proximity to the city centre. In this context, questions arise, such as: What happens if citizens collectively engage at a stage where a clear project has not yet evolved, thereby attempting to take user-generated development serious from scratch? How can communication to private owners and developers of large-scale brownfield sites improve? To what extent can a collective citizen initiative guide the process in the triangle between private owner and investor, local council and planning administration and the citizens?

Citizen initiative for brownfield transformation in Dortmund

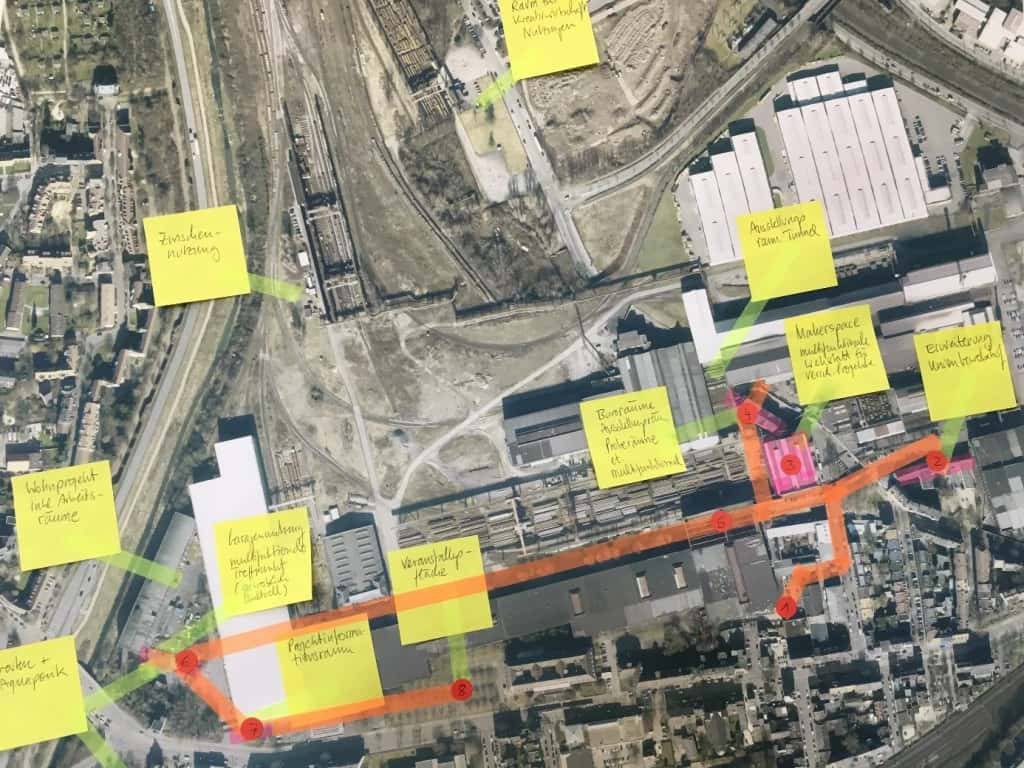

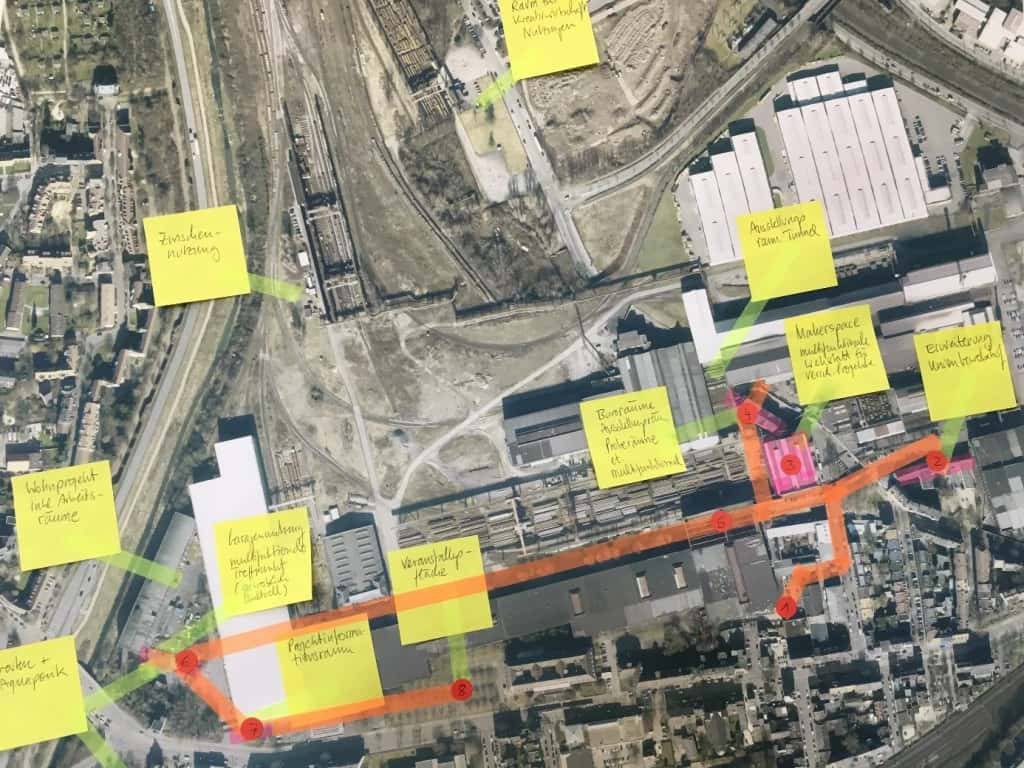

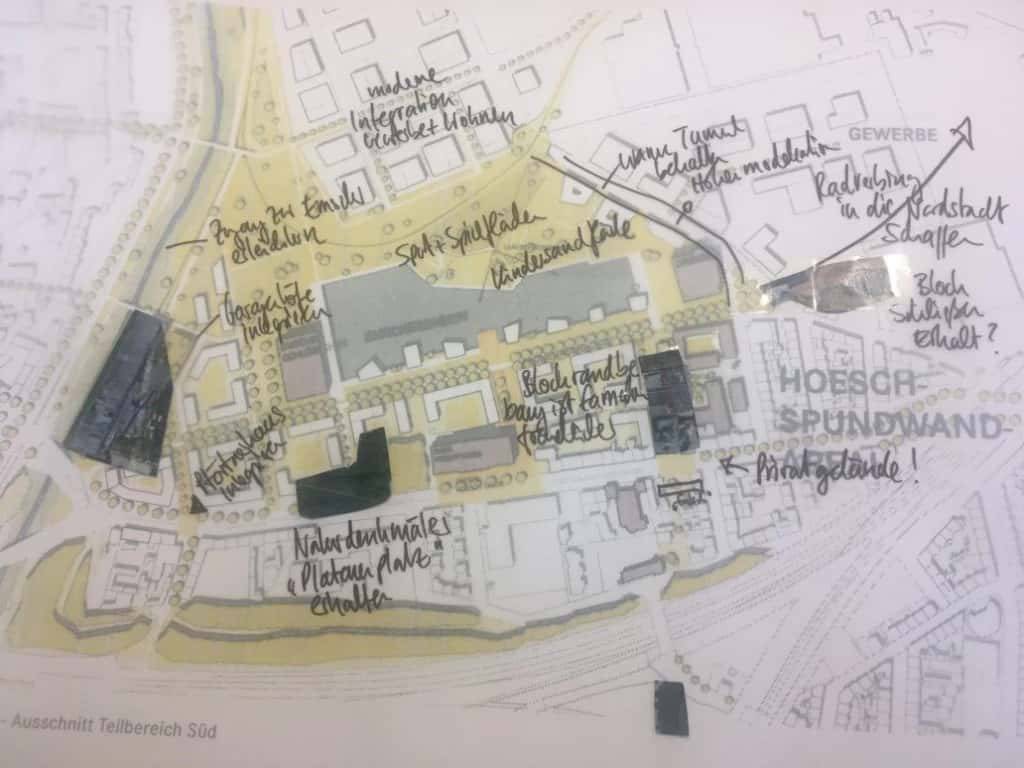

The neighbourhood (part of the so-called 'Unionviertel') has a diverse and multi-cultural population. It had a high fluctuation rate of inhabitants and a high unemployment rate when the last part of sheet piling production on the site stopped at Christmas 2015. The building structure is characterised by a dense housing block structure and large-scale former industrial areas (see figure 1). The southern edge of the site is central and accessible, but mostly known as a drive-through area. The neighbourhood is also home to the community initiative and local association 'Die Urbanisten e.V.', which is engaged in urban projects in Dortmund and the region and that hosted NWU from the beginning It was founded in 2010 by a group of people working at the interface between urban development, education, arts and culture.

Civil society initiatives of this kind are not new. What is interesting in this context is their occurrence in a setting with a vested interest by the city government, strong tools within the legal planning system and a regional-based property owner and developer. The activists strive to open an integrative process (user-generated urban development) for such a large vacant site before any informal or formal planning process is kicked off. In this case, the initiative started developing ideas even before production finally terminated, the property was sold and the issue was put on the political agenda.

Organisation, communication and action of NWU

The initiative NWU has its origins in 2015 when the industrial site of the steel construction company Hoesch Spundwand & Profil (HSP) in Dortmund finally closed and laid off its last workers. Ownership had then been transferred to a private company that owns many old industrial sites in the region (Thelen Group, based in Essen). In 2016 a group of students, artists, spatial planners, and neighbours decided to act and formed the NWU. They actively approached the new private owner with suggestions for a possible process design (Noltemeyer/die Urbanisten 2020). The initiative aimed to develop their urban neighbourhood and not passively wait for the private property owner to present ideas. In other terms, they build a legal and collective form of activism aimed at political participation in a loosely organised and network-based form (Ekman/Amnå 2012: 292).

The group met in irregular intervals to exchange information on topics related to a possible future development (full timeline in German in Noltemeyer/Die Urbanisten 2020). The initiative started to sketch their needs and ideas and the needs of the local community and collected them systematically since 2017 (see an example in figure 2). By self-organising information and participation events (information evenings, community cafés, viewings and site visits and cultural events), the initiative attempts to open the process to the local community. They also involved groups of students in projects and urban design studios and in individual Bachelor and Master theses.

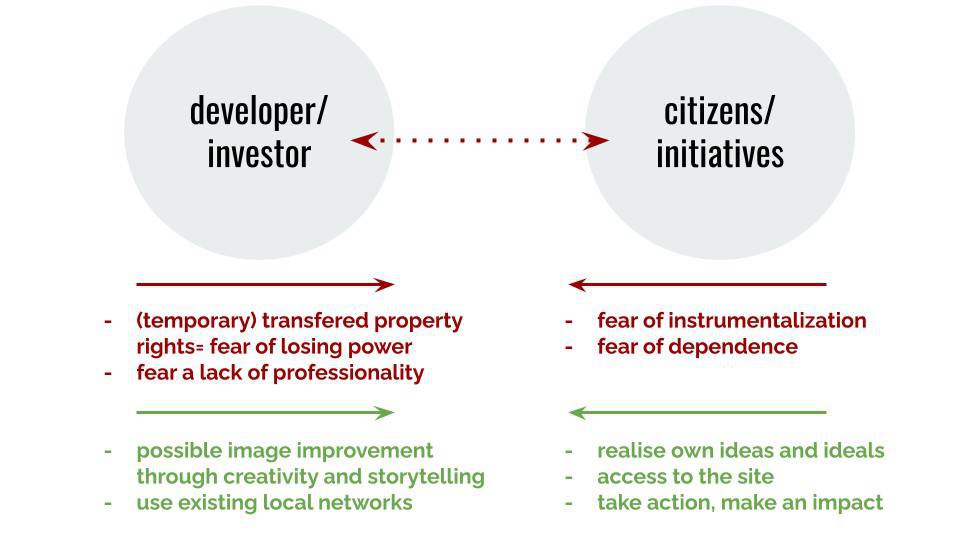

The different organisational structures, target systems and motivations for action also reveal different expectations of those involved in the project development processes (see figure 3). Whilst the availability of capital and property provides owners and investors with strong power, they often lack local expertise. Initiatives on the other side act on a voluntary basis, are committed to the project and willing to take risks and focus on immediate actions. Their greatest ability is their social capital: local ties, networks, relationships, and particularly strong local knowledge. In this case, the active local networks made the organisation of some (international) events possible. The site was, for instance, part of the venue for an art festival, which brought together artists, curators, and scientists for a joint exchange. In discussions with former workers and the current neighbourhood, artists explored which untold stories, utopian realities and futures can be found behind the facade of the old factory walls. Furthermore, the student associations for urban and regional planning organised their biannual conference on the site, which brought together more than 200 international students to discuss future urban development in workshops and excursions.

As a loosely organised network of activists that work within legal boundaries of activism (Ekman/Amnå 2012), it takes effort and time to be heard. Urban development processes depend on many external (soft) factors, such as the current political situation, personal relationships, or the real estate market. In user-generated developments, initiatives like NWU need to act first to make an impact. One major challenge that initiatives often face is the organisation structure. None of the members is professional or receives financial benefit for the engagement. Also, active members are constantly changing over time because of the long-time dimension of the urban development project. Members of the initiative need to be consistent and cohesive, share the same aim and support each other in the group. It is useful to find a fixed organisational structure that makes communication channels clear and reduces fears of instrumentalization and dependence. Clear organisational structures, defined objectives and transparent communicational structures help to build legitimacy, credibility, and trust from the negotiating partner. The developer, but also the city government, does not easily recognise an open network structure as an equal partner.

In the case of Dortmund, the development was taken a step forward in 2019 by the property owner and the city government, using the label 'Smart Rhino' (Thelen-Gruppe 2020). It includes the International Garten Exhibition in 2027, relocating a campus area of the university of applied sciences and a mix of housing, commercial and recreational uses.

The concept differs remarkably from NWU ideal types. It does not show open exploratory spaces that can be (temporarily) filled by community actors. It shows a central lake that resembles another redevelopment project in southern Dortmund (Phoenix Lake). Relocating the campus area was a surprise and not much thought of by NWU before. However, the 'Smart Rhino' concept also takes up parts of the rhetoric around the area and aims to deliver an integrated urban neighbourhood that is developed in an inclusive process with the community. While earlier ideas of the developer paid little attention to any of the old building structures, the aim is now to include a few of the old buildings at the edges. It remains to be seen how much the engagement of many NWU members will change the actual development and influence the spending of private and public money for this site. As further steps of official participation processes unfold, NWU makes use of its communication channels and will also hold more argumentative power to bring forward their concerns.

What, if…? Closing a triangle by mutual communication and cooperation!

Future urban development cannot succeed in a top-down manner against local protests, polarisations, and neighbourhood qualities. In a post-industrial setting like Dortmund, development should not rely on (inter)-national prospects but needs to develop futures for its population. Future urban development cannot succeed in a top-down manner against local protests, polarisations, and neighbourhood qualities. With an abundance of unused large sites in semi-public and private ownership, cooperation between public administration and civil society alone does not suffice. The co-design of public services and the turn from expert-driven to user-driven ideas already provide promising pathways (Trischler et al. 2019). However, the link between citizens and citizen initiatives and developers and investors of vacant sites is yet under-researched (figure 3 & figure 5).

Understanding this part of the triangle is especially important where a public planning authority prevails that has formal powers (planning/project approval for developers), a public mandate for its citizens (accountability), but limited resources on its own. The neighbourhood around the site holds a working and migrant population that cannot bring in the necessary resources for a medium or large-scale change.

Such a closure offers mutual benefits: citizens and initiatives are potential users (and customers, in economic terms) and they keep any development site lively (and valuable) throughout its lifetime. In the case of NWU, their interest was to implement temporary uses and projects immediately and learn from immediate experiences. Through their strong local ties and knowledge of the existing networks and structures, they are the experts on site. Civil initiatives can often immediately start as temporary users and do what is most important: opening spaces for use by people and small-scale entrepreneurs (Chang 2019). This gives immediate meaning and quality to a site (and its maintenance also keeps the economic value). Initiatives can give properties a new story and a new image – a fact that needs careful consideration not to be misused for pure economic benefits. Over a lifetime, the neighbourhood around that site will be major users. So, what makes it difficult to be on the same side and work as equal partners?

Outlook: taking citizen initiatives as partners

NWU in Dortmund is an example of a civil society initiative that formed as a loose network to be an equal partner in the development of a large vacant former industrial site. NWU in Dortmund started with ambitious aims and made its steps to be heard, but also encountered struggles in establishing communication channels. Early communication between civil society and developers – even before development ideas materialise – should become a standard to open spaces for immediate use and to develop creative long-term ideas that go beyond copy-paste solutions. Larger changes in planning cultures would be needed to fulfil bolder demands. This also requires a fundamental rethinking of the traditional planning profession that participates but gives up powers to initiate and guide planning processes.

One task should be to organise cooperation between individual actors and thus, for example, organise temporary agreements (e. g. projects for temporary use; see Chang 2019). These changes could lead to improved – more resilient and sustainable – urban development processes, also regarding possible crises, such as the current corona pandemic. The local level with the knowledge of its citizens is crucial for the successful long-term development of our cities. Especially in times of crisis, it becomes clear that local living conditions have become even more important and that active participation and recreation of the cities by its inhabitants is necessary to create healthy environments. Encourage civil society to act in a joint planning culture to regenerate & redevelop – learn from post-industrial transformation projects such as the one presented in this article to transform neighbourhoods. In short, encourage and get active!

Author profiles

Silja Kessler, M.Sc., studied both Spatial Planning (M.Sc., TU Dortmund) and International Development Studies (M.Sc., Utrecht University). She worked in the field of participatory planning in Dortmund and Berlin. Her research interests are participation processes, civil society empowerment, and user-generated urban development. Contact:

Dr. Christian Lamker is an Assistant Professor of Sustainable Transformation & Regional Planning at the University of Groningen (Netherlands). His research and teaching focus on roles in planning, post-growth planning, regional planning, and leadership in sustainable transformation. He has studied and worked on spatial planning in Dortmund, Aachen, Auckland, Detroit, and Melbourne and coordinates the Master programme Society, Sustainability and Planning (SSP) in Groningen. Contact:

Bibliography

Chang, R. (2019, October 23). Conversational Cuts on Exploring the Intersections between Post-Growth Planning and Temporary Urbanism. Insights following our international panel discussion in August 2019. EPC Conversational Cut. http://epc.tu-dortmund.de/wordpress/en/conversational-cuts-on-exploring/

Ekman, J., & Amnå, E. (2012). Political participation and civic engagement: Towards a new typology. Human Affairs, 22(3). https://doi.org/10.2478/s13374-012-0024-1

Healey, Patsy (2015): Citizen-generated local development initiative: recent English experience. In International Journal of Urban Sciences 19 (2), pp. 109–118. DOI: 10.1080/12265934.2014.989892.

Noltemeyer, Svenja; Die Urbanisten (2020): Neue Werk Union – ein neuer Stadtteil entsteht. Die Urbanisten. Dortmund. Available online at https://dieurbanisten.de/urbanisten-projekt/kreative-stadtentwicklung-auf-dem-ehem-hsp-areal, checked on 8/6/2020.

Thelen-Gruppe. (2020). Thelen-Gruppe | Smart Rhino. https://www.thelen-gruppe.com/portfolio/projekt/smart-rhino/

Trischler, Jakob; Dietrich, Timo; Rundle-Thiele, Sharyn (2019): Co-design: from expert- to user-driven ideas in public service design. In Public Management Review 21 (11), pp. 1595–1619. DOI: 10.1080/14719037.2019.1619810.

Willinger, Stephan (2014). Governance des Informellen. Planungstheoretische Überlegungen. In Informationen zur Raumentwicklung (2), pp. 147–156.

Further readings

Bömer, H., & Zimmermann, D. (Eds.). (2010). Dortmunder Beiträge zur Raumplanung – Blaue Reihe: Vol. 135. Stadtentwicklung in Dortmund seit 1945: Von der Industrie- zur Dienstleistungs- und Wissenschaftsstadt. IRPUD, Institut für Raumplanung, TU Dortmund, Fakultät Raumplanung.

Boonstra, B., & Boelens, L. (2011). Self-organization in urban development: towards a new perspective on spatial planning. Urban Research & Practice, 4(2), 99–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/17535069.2011.579767

Chang, Robin; Lamker, Christian Wilhelm; Kessler, Silja (2020): Resilience Trade-Offs: A Dortmund Tale of Tribulations with Informal Initiatives and Inclusionary Processes. In Christa Reicher, Fabio Bayro-Kaiser, Paivi Kataikko, Sarah Müller, Jan Polivka (Eds.): Urban Integration: From Walled City to Integrated City. Conference proceeding. Münster: LIT (Stadt- und Raumplanung/Urban and Spatial Planning, 19), pp. 36–39.

Chang, R. (2017, September 19). How 'temporary urbanism' can transform struggling industrial towns. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/how-temporary-urbanism-can-transform-struggling-industrial-towns-75114

Igalla, M., Edelenbos, J., & van Meerkerk, I. (2019). Citizens in Action, What Do They Accomplish? A Systematic Literature Review of Citizen Initiatives, Their Main Characteristics, Outcomes, and Factors. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 30(5), 1176–1194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-019-00129-0

Kessler, Silja (2018): Informeller Urbanismus zwischen Zivilgesellschaft und Investoren. Fallbeispiel Neue Werk Union, Dortmund. Master thesis. TU Dortmund, Dortmund. School of Spatial Planning.

Nellen, D., Sonne, W., & Wilde, L. (Eds.). (2018). Dortmund bauen: Strategien und Perspektiven der Dortmunder Stadtentwicklung im 21. Jahrhundert. Jovis Berlin.

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.

Comments