On participation and neighbourhood planning

I recently stumbled upon a talk given by Chilean architect Alejandro Aravena at TED Global 2014. Having to come up with solutions for building adequate homes for 100 families, Aravena decided on splitting tasks with the local community, in which the publicly provided half-house was complemented by another family-provided half. Working with the communities enabled the task force to innovate and come up with solutions in the context of limited budgets and restricted land supply.

Elemental - Alejandro Aravena. © Cristobal Palma

Elemental - Alejandro Aravena. © Cristobal Palma

Although innovative in terms of design, Aravena’s work draws heavily on principles of urban planning which have largely been advocated in the past decades. Moving from master planning to collaborative planning and an increased role for communities has been advocated by a wide range of academics and organisations. Some have focused on creating tools for place-making design processes, others have worked on creating methods for engaging a wider audience in urban planning. But scepticism remains as to whether these instruments are able to move forward from collaborative design to challenge the unequal relations in cities themselves.

In the UK, the Localism Act introduced in 2011 by the Coalition government enabled citizen groups to come up with Neighbourhood Development Plans. Apart from abolishing the regional planning layer (with the exception of Greater London), the bill aimed to put people back at the centre of decision making. Local communities go through a series of stages including forming a neighbourhood forum, designating an area, preparing a neighbourhood plan and a local referendum before its actual implementation. But they thus have the opportunity to make decisions locally on allocation of land for housing, retail or office space.

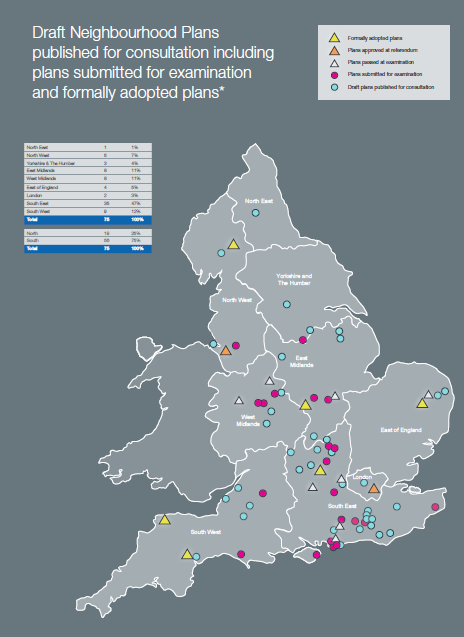

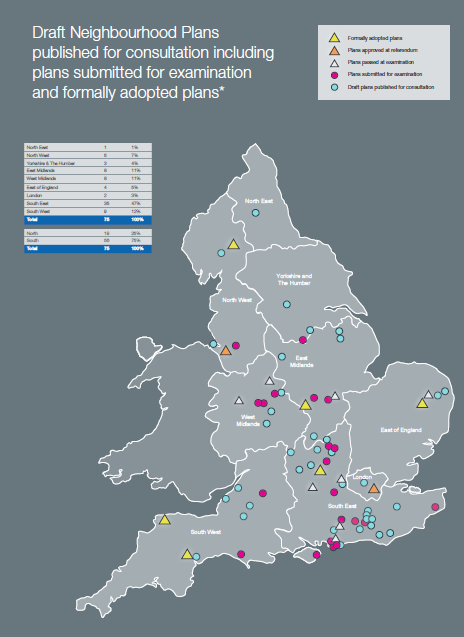

Could this be the long awaited shifting of power towards local communities? Some caution is required here, if we take into account at least 3 factors: (1) neighbourhood plans cannot go against higher tier planning documentation; (2) the actual implementation of Neighbourhood Plans is still at a very early stage; (3) according to a Turley report more Conservative and affluent areas have been most proactive so far in creating Neighbourhood Forums. This means that “participation for all” is not yet a reality and that neighbourhood planning must find the necessary levers to go beyond “the usual suspects” and beyond areas that benefit from higher social capital.

Map of draft neighbourhood plans. © Turley

Map of draft neighbourhood plans. © Turley

But if in the UK this type of change was rather triggered “from above”, through increased devolution of power, in countries with less established democratic systems changes are more likely to come “from below”. International media has covered in the past year extensive protests in Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary and Turkey signalling a wave of discontent and demands for more democratic and transparent systems. Will these filter down to the local level as well and is it possible that reactive movements can turn into proactive ones, enabling citizens to engage long-term in drafting of local plans?

Last week, following national turmoil on the Romanian presidential elections, a few hundred citizens pushed for the dropping of a project planned on green space in the East of Bucharest. The Local Council had approved a detail plan for a public cultural hall in the park. Although mapped as green area, the land is privately owned by the municipality which is not legally obliged to maintain the land status as green space, even though the Sector’s level of 16 sqm green space per capita is considerably below the 26 sqm/capita EU standard. Local discontent on reducing green space, coupled with the unfavourable political climate has triggered the Municipality decision’s to rethink its decision, but the project remains a priority once suitable land has been found.

Protest, Bucharest, 22 Nov 2014. © Anca Cernat

Protest, Bucharest, 22 Nov 2014. © Anca Cernat

Going back to the example of Aravena’s work in Chile, what was essential in the success of the project was the cooperation between the task force – working on the municipality’s behalf – and the local community. This starts with the need to better define and work with tools guaranteeing participation in every stage of a planning project – from concept to implementation. That is something that the Localism Act guarantees in the UK, in spite of its limitations mentioned before. Even though local communities usually cannot resists targets imposed from above (for example, in terms of building of new housing units), it does have the power to decide what and where is built. For Central and Eastern European countries, however, participation has to start at the very basic level of making information available on what planning is and what its instruments are. And it starts with laying grounds for a common language of talking about the city.

[to be continued]

Elemental - Alejandro Aravena. © Cristobal Palma

Elemental - Alejandro Aravena. © Cristobal PalmaAlthough innovative in terms of design, Aravena’s work draws heavily on principles of urban planning which have largely been advocated in the past decades. Moving from master planning to collaborative planning and an increased role for communities has been advocated by a wide range of academics and organisations. Some have focused on creating tools for place-making design processes, others have worked on creating methods for engaging a wider audience in urban planning. But scepticism remains as to whether these instruments are able to move forward from collaborative design to challenge the unequal relations in cities themselves.

In the UK, the Localism Act introduced in 2011 by the Coalition government enabled citizen groups to come up with Neighbourhood Development Plans. Apart from abolishing the regional planning layer (with the exception of Greater London), the bill aimed to put people back at the centre of decision making. Local communities go through a series of stages including forming a neighbourhood forum, designating an area, preparing a neighbourhood plan and a local referendum before its actual implementation. But they thus have the opportunity to make decisions locally on allocation of land for housing, retail or office space.

Could this be the long awaited shifting of power towards local communities? Some caution is required here, if we take into account at least 3 factors: (1) neighbourhood plans cannot go against higher tier planning documentation; (2) the actual implementation of Neighbourhood Plans is still at a very early stage; (3) according to a Turley report more Conservative and affluent areas have been most proactive so far in creating Neighbourhood Forums. This means that “participation for all” is not yet a reality and that neighbourhood planning must find the necessary levers to go beyond “the usual suspects” and beyond areas that benefit from higher social capital.

Map of draft neighbourhood plans. © Turley

Map of draft neighbourhood plans. © TurleyBut if in the UK this type of change was rather triggered “from above”, through increased devolution of power, in countries with less established democratic systems changes are more likely to come “from below”. International media has covered in the past year extensive protests in Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary and Turkey signalling a wave of discontent and demands for more democratic and transparent systems. Will these filter down to the local level as well and is it possible that reactive movements can turn into proactive ones, enabling citizens to engage long-term in drafting of local plans?

Last week, following national turmoil on the Romanian presidential elections, a few hundred citizens pushed for the dropping of a project planned on green space in the East of Bucharest. The Local Council had approved a detail plan for a public cultural hall in the park. Although mapped as green area, the land is privately owned by the municipality which is not legally obliged to maintain the land status as green space, even though the Sector’s level of 16 sqm green space per capita is considerably below the 26 sqm/capita EU standard. Local discontent on reducing green space, coupled with the unfavourable political climate has triggered the Municipality decision’s to rethink its decision, but the project remains a priority once suitable land has been found.

Protest, Bucharest, 22 Nov 2014. © Anca Cernat

Protest, Bucharest, 22 Nov 2014. © Anca CernatGoing back to the example of Aravena’s work in Chile, what was essential in the success of the project was the cooperation between the task force – working on the municipality’s behalf – and the local community. This starts with the need to better define and work with tools guaranteeing participation in every stage of a planning project – from concept to implementation. That is something that the Localism Act guarantees in the UK, in spite of its limitations mentioned before. Even though local communities usually cannot resists targets imposed from above (for example, in terms of building of new housing units), it does have the power to decide what and where is built. For Central and Eastern European countries, however, participation has to start at the very basic level of making information available on what planning is and what its instruments are. And it starts with laying grounds for a common language of talking about the city.

[to be continued]

Stay Informed

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.

Comments 3

Thank you for this really inspiring post, Irina, and let me share some thoughts on the case of UK. It is not useless to remind that the Localism Act has been introduced by a centre-right government and that it is part of wider efforts for the so-called "Big Society", that is, an attempt at reducing state. Critiques about how discourses about participation and empowerment are crucial to neoliberal governmentalities are far from new, as a matter of fact. And some have recently debated how this new localism, especially in a country where cities are especially segregated, may bring about further polarization (cf., e.g., http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02697459.2012.699228#.VHdqm9KsWSo). This because the "units" for public policy are so small that they tend to be homogeneous, hence with significant different power and resources (and, as you write, it is on richer neighbourhoods that participation is taking place). Add the curtailing of austerity budgets to this, and you have the full picture.

This has implications for participation in general, which, in my opinion, has a two-fold (or manifold) gist, which can be unravelled only when looking at it in the picture of public policy (especially in territorial and social cohesion) and political arrangements in general.

[…] a previous post, I was writing about participatory practices in urban development, particularly from the point of […]

[…] taken-for-granted basis. Yet how much are places are a reflection of who we really aspire to be? People’s ability to effectively shape places in ways that are meaningful to them can face multiple hurdles. Politics and power can enable as […]