Literature reviews at odds: Between conflict management and information overload

10 min. read

Introduction

In the first article in this series, I discussed the importance of starting and ending with why, and how a fit-for-purpose strategy can help deliver a meaningful contribution to knowledge. This, even as the odds of research projects may lead one off the beaten-track and into the great wilderness of the 'Unplanned'. The capacity to manage conflict and information overload are equally important to deliver an engaging literature review or state-of-the-art – for researchers and industry professionals alike. Does conflict sound bad enough? Actually, it gets worse in the section after.

Managing conflicting interests

Invariably, strategy, as explored earlier, is tied to conflict management. You will probably have heard from combat experts such as Dwight Eisenhower, Winston Churchill, Colin Powell, Moltke the Elder, or even Mike Tyson that "a plan never survives first contact with the enemy". As human disasters constantly remind us, peace is the foundational pre-requisite and goal of any sound spatial planning endeavour. One may not wish to view planning practice and research in a kind of 'combat' mode, although some forensic architecture firms have made it their mission to redeem justice from aggression in an objective manner. Some nations have also famously declared, or are considering joining, a 'war on climate change', and planning certainly has everything to do with our capacity to mitigate and adapt to climate change. In the UK, as elsewhere, organisations such as UK100, Ashden and mySociety have made it clear that local authorities have the opportunity to ground the climate transition across society. So, although we would rather do without it, we cannot escape the conflict. Conflicting interests must somehow be managed for any planning outcomes or research outputs to come about. Conflict lies at the heart of planning.

One ideal textbook description of spatial planning is a coherent system that seeks to harmonise competing interests in how space and places are designed and managed – for lack of any authoritative definition (see Parker & Street, 2021). For example, this tension is clearly illustrated throughout countless national planning policies, such as Transforming Places Together, which outlines the digital planning strategy for Scotland (2020):

"To do planning well, we need to carefully interrogate a great deal of complex information and data, to listen intently to different perspectives and to act both swiftly and fairly in making what can sometimes be pressured and difficult decisions."

A fundamental aim of spatial planning in many parts of the world is to manage competing land uses and stakeholder interests while striving to implement national policy orientations in the presumption of sustainable development, such as net zero carbon policies, national regeneration strategies, or improving biodiversity. How much spatial planners actively own up to the role of 'conflict mediators' in support of the climate transition remains a matter of contention (UK100, 2021). Be it in from the perspective of sustainable transport, affordable housing, decarbonised infrastructure, or sustainable farming, there is nothing environmentally 'neutral' about planning policy and practice, as it provides a broad avenue for sustained, cross-sectoral climate action at the local level and regional level.

While conflict cannot ever be diffused completely, there are opportunities to manage and channel it in creative, fruitful ways. Be it through agonism, antagonism, pragmatism, critical utopianism, or other means, one has to find ways to make planning work in the face of conflict (Forester, 2006, 2013; Healey, 2012; Mouffe, 1999; Swyngedouw, 2011). At least in theory, evidence-based and data-driven planning generally aim to improve society by resolving conflicts in interests and improving decision-making rather than increasing conflict or bias (Boland, Durrant, McHenry, McKay, & Wilson, 2021; Faludi & Waterhout, 2006). The gathered evidence can help make places and spaces more 'urbane' and civilised overall. Even if this evidence is conflicting and pulls in different directions (e.g. NIMBY vs YIMBY), as can be the case in reviewing public participation input for metropolitan planning (Kahila-Tani, Broberg, Kyttä, & Tyger, 2016). However, if the evidence does not fit in a single filing cabinet – as may be the case of printed metropolitan plans that occupy an entire room – updating it can be a messy task. Planning teams need pretty good document versioning, information retrieval, communications and community engagement skills to keep the plan in one piece. This could explain the drive for digital planning systems across Europe and beyond.

The messiness of research is a reflection of the world it investigates. Research projects and careers are messy and rarely go according to plan. There may be a million reasons for this. These can exacerbate the inherent conflict of scoping a literature review, in that one must renounce vast swathes of knowledge to focus on a well-bounded micro-set of issues. Such is the tyranny of choice and the related analysis paralysis that may conflict with our innermost desire for simplicity, made only worse by the researcher's fear of missing out because, indeed, many 'tangential' topics are fundamental and not just 'interesting'. However, they will never fit in a 6,000-8,000 word article.

The above discussion reveals the elephant in the room, which is none other than information overload. It is probably the greatest source of mental ill health and conflicting knowledge that plagues individual researchers and entire professions alike.

Information overload

We've known since at least the 1990s that we live in the so-called Information Age of the (hyper-) networked society (see the eponymous work by Manuel Castells). In 2022, the Information Age translates as Internet 3.0 with tailored advertisements, an app-driven approach to work and collaboration, Digital Twins, ubiquitous sensors across the built and natural environment, (very) Big Data, semantically linked data, increased automation & digitisation in planning and construction, and super-productivity apps that may lower your overall productivity. Thanks to social media and connectedness through smartphones and other portable devices, we all carry loudspeakers that also function as telescreens, right in our pockets wherever we go. We now consume more 'information' in days than was previously produced over millennia. The combined pressures of 'publish and/or perish', the growth in the number of PhD positions without long-term academic career prospects, and the associated growth in the overall number of research publications, threaten our capacity to process and contribute meaningful information to the world. Information overload not only makes people ill or anxious, it can also lead to shallow information and poorer decisions (Bawden & Robinson, 2009; Melinat, Kreuzkam, & Stamer, 2014; Roetzel, 2019). Information overload is our default state as knowledge workers, yet it also kills the knowledge before we can even work with it. There's a lot of data out there, and it's not always clean. What's knowledge if we can no longer differentiate information from noise or if we mainly come to know the real world through a digital screen? Is the physical world now modelled on the Metaverse rather than the other way around? By extension, how do we 'keep it real' as researchers?

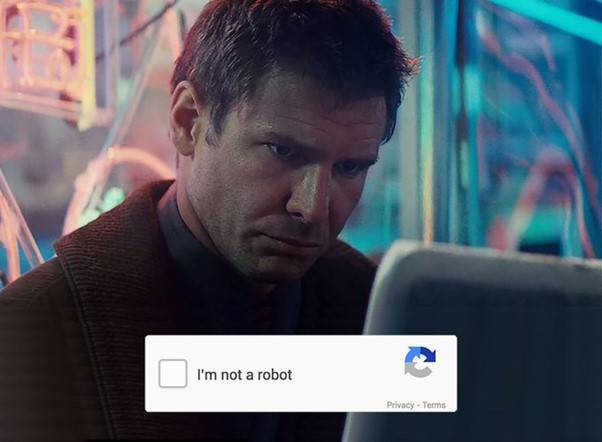

Information retrieval for literature reviews can leave one quizzical and existentially perplexed about how to manage unmanageable amounts of information – while keeping it real and remembering who we are. Watch the iconic film again, or, better still, read the seminal novel.

Researchers in medieval Europe were already complaining about having too much to read. More and more information has been piling up to this very day (Bawden & Robinson, 2020). Quite appropriately, Monty Python released a sketch in 1970 about the prowess of the Royal Society For Putting Things on Top of Other Things. As you may hear directly from John Cleese at the very end of the sketch, some people (allegedly in Staffordshire, England) may have found the act of piling more things on top of more things a rather silly exercise. Today, slow academia tries to redeem sustained, quality research from the cloud of noise and shallow semi-automatable research outputs created by digital information overload and the pressure to publish at all costs. This can come at the very cost of providing a valuable contribution to knowledge, which is the 'why' of doing research in the first place. An underpinning principle of minimalism in architecture, graphic design, interior design and lifestyle choices is that more is never enough, and so, therefore 'less is more'. What is the scope for impactful knowledge if impact criteria undermine quality knowledge itself? Perhaps wisdom is (still) the missing bit of the jigsaw, depending on how it may be construed.

"The saddest aspect of life right now is that science gathers knowledge faster than society gathers wisdom."

― Isaac Asimov

Perhaps conflicting types and quantities of information should be managed in the best imperfect way possible, which defies all researchers' and decision-makers compulsion for clarity, neatness, and simplicity in a world that is inherently complex, entropic, and struggling to connect the dots in the face of the climate emergency. A good story is never as clear or predictable as it might initially seem because it seems more real and less fabricated. The trick, then, is finding ways to extract meaningful, relevant information in moderate, digestible amounts while not entering the wormhole of near-continuous information overload, which is the sure death of our frail, limited human mind. The San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment may perhaps slowly (eventually) push research impact beyond the narrow, arcane confines of journal 'impact factors'.

Information overload will put you through unmanageable states. This perennial predicament calls for a proper Resarchers' Mental Health for Information Retrieval and Processing Survival Toolkit. Image credit: 'Sensory Overload', photo of mural in Eastern Market, Detroit by Chris Christian on flickr.com.

In the final analysis, managing information overload is an uphill battle that is lost even before our best plan encounters the enemy. It is like Sisyphus's curse to eternally push a rock up a hill and let it roll back down again and again. Or like the forever elusive Eldorado or mirage that makes you forget the ground you are standing on. The obsessive pursuit of an external, desired object may leave one to forget why it is sought in the first place. Likewise, the 'publish and/or perish' motto may be like trying to deliver projects 'the day before yesterday', which is a common predicament for countless industry consultants and software programmers. This absurd predicament could be the inspiration for transformative creativity. It echoes with 'Tangerine Dream', the German-English pun that plays with the German words baum and traum, which became the name of the pioneer electronic music band. Tangerine Dream's founder Edgar Froese allegedly suggested: "In the absurd often lies what is creatively possible".

Welcome to the age of quantum information. We acutely rely on the machines which co-created our default state of Information Armagedon to help us sort it out. Picture credit: photo by Fly:D on Unsplash.

So clearly all our hopes are not lost to the information wormhole of modern academic and market research. We could in fact become creative about the whole thing, even if the cannons of academic publishing may not always allow it.

From conflicting information to knowledge management

As might be apparent, I don't have any ready-made answer to these predicaments of managing conflicting interests or excessive amounts of information. Nor could I find any in the literature, apart from two ways of coping with information overload, kindly shared by Bawden and Robinson (2020): 1) filtering (less relevant) information; and 2) avoiding it altogether. Thinking of it, the latter could also be called procrastination, though the authors indicate it could be more a case of selective exposure (i.e. bias) from avoiding information we don't like. I certainly have first-hand experience of information withdrawal, which the authors indicate can be a cheap but effective coping mechanism. Somewhat similar to when digital natives go on social media fast for, say, thirty days. The likelihood is, you probably know how to manage the right amounts and quality of information much better than I do. Still, simple hacks might not realistically preserve one's sanity as a researcher, given the seemingly exponential pace of data and information production, and the competitive numbers game of publishing… Alternative sources of inspiration, which are simultaneously more ludicrous and fruitful, can be found in science fiction, mythology, electronic music and British humour from the 1970s, as hinted in this article – or whatever rocks your boat. Research is always unfinished work (even when large projects formally come to an end): there will always be more to do. And when information accumulation just goes on and on, mind-numbingly, it seems that more is always less.

An 'essentialist' or 'minimalist' approach to literature reviews and knowledge management more generally, could be a promising, fruitful avenue to deliver more intentional value. The latter, even as planning research and practice remain complex. As a recovering perfectionist, an essentialist approach to conducting literature reviews seems both a practical impossibility and a moral necessity. I suggest listening to Tangine Dream's What You Should Know About Endings about how to wrap up any piece of seemingly unfinished (or unfinishable) work, such as this one.

In sum, a good strategy heightened by an awareness of how to deal with inherent conflict and excessive amounts of information reminds us that design makes choices imperfect. You could also call that risk management. Nonetheless, once a choice has been made, one does need to stick it to guarantee internal coherence while preserving one's mental health, the latter being arguably more important than the former. So, 'less is more,' as goes the minimalist, somewhat counter-intuitive equation:

↓ = ↑

As discussed above, the corollary is also true!

May the odds be with you

To paraphrase Yoda's advice and wishes to a young aspiring Jedi many, many sabre light years ago, I sincerely wish everyone that the odds may always be supportive because research appears to me as one long uphill battle. So beat the odds and courageously own up to what may be, rather than trying to manage the chimeric beasts of perfection or predictability.

The next articles will share five main ways of conducting literature reviews and simple knowledge management strategies.

If you have achieved stellar knowledge management in your own research, do share your experience with the wider community and get in touch at:

REFERENCES

Bawden, D., & Robinson, L. (2009). The dark side of information: overload, anxiety and other paradoxes and pathologies. Journal of Information Science, 35(2), 180-191. doi:10.1177/0165551508095781

Bawden, D., & Robinson, L. (2020). Information Overload: An Overview. In Oxford Encyclopedia of Political Decision Making. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Boland, P., Durrant, A., McHenry, J., McKay, S., & Wilson, A. (2021). A 'planning revolution' or an 'attack on planning' in England: digitization, digitalization, and democratization. International Planning Studies, 1-18. doi:10.1080/13563475.2021.1979942

Faludi, A., & Waterhout, B. (2006). Introducing evidence-based planning. DISP, 165(2), 4-13. Retrieved from https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-33749381148&partnerID=40&md5=2f0b48161042540e6b0f0abdb60ec7f8

Forester, J. (2006). Making Participation Work When Interests Conflict. Journal of the American Planning Association, 72(4), 447-456. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=vth&AN=23071562&site=ehost-live

Forester, J. (2013). On the theory and practice of critical pragmatism: Deliberative practice and creative negotiations. Planning Theory, 12(1), 5-22.

Healey, P. (2012). Re-enchanting democracy as a mode of governance. Critical Policy Studies, 6(1), 19-39. doi:10.1080/19460171.2012.659880

Kahila-Tani, M., Broberg, A., Kyttä, M., & Tyger, T. (2016). Let the Citizens Map—Public Participation GIS as a Planning Support System in the Helsinki Master Plan Process. Planning Practice & Research, 31(2), 195-214. doi:10.1080/02697459.2015.1104203

Melinat, P., Kreuzkam, T., & Stamer, D. (2014, 2014//). Information Overload: A Systematic Literature Review. Paper presented at the Perspectives in Business Informatics Research, Cham.

Mouffe, C. (1999). Deliberative Democracy or Agonistic Pluralism? Social Research, 66(3), 745-758. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40971349

Parker, G., & Street, E. (Eds.). (2021). Contemporary planning practice: Skills, specialisms and knowledge. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Roetzel, P. G. (2019). Information overload in the information age: a review of the literature from business administration, business psychology, and related disciplines with a bibliometric approach and framework development. Business Research, 12(2), 479-522. doi:10.1007/s40685-018-0069-z

Swyngedouw, E. (2011). Interrogating post-democratization: Reclaiming egalitarian political spaces. Political Geography, 30(7), 370-380. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2011.08.001

UK100. (2021). Power Shift: Research into Local Authority Powers Relating to Climate Action. Retrieved from https://www.uk100.org/publications/power-shift

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.

Comments