Concrete-stop: from metaphor to reality

Guest author: Clemens de Olde, University of Antwerp

The new Spatial Policy Plan for Flanders hasn’t been approved by the Flemish Government yet, but it has already stirred up quite a media storm. Since its first announcement it has become known as the “concrete-stop” (betonstop). As more details emerge, the intent to completely stop building in open space by 2040 has become the token measure of the entire plan. The fact that exactly this element has caught on says a lot about planning culture in Flanders. Why has the concrete-stop become so mediagenic?

Link: for more background on the changes afoot in the Flemish planning systems read my first blog

The Power of Metaphor

Metaphors are essential in presenting planning to a wider public. Famous examples include the Dutch Randstad or the European Blue Banana. Flanders too, has its planning metaphors. The Flemish Diamond, which was presented in the 1997 Structure Plan as a “precious gem” to represent the region’s core economic area between the cities of Antwerp, Ghent, Brussels, and Leuven.

The use of metaphors can bring actors together in a development strategy but they are never neutral. Dühr, Colomb & Nadin define preparing spatial concepts as a political act that favours and promotes certain interests:

‘Who is involved in the preparation of the spatial concept, and which spatial information is selected to represent it, will thus significantly affect the message’ (2010, p. 56).

And now there is the metaphor of concrete-stop as popular moniker for the new Spatial Policy Plan. It represent the intent of the plan to reduce and halt the “additional daily intake of open space” from 6 hectares currently, to 3 hectares in 2025, to 0 in 2040 (Vlaamse Overheid, 2016). This implies a large operation of rezoning land currently marked for housing development, and stimulating densification in the urbanized areas. That seems at odds with what De Decker (2011) has described as “the compulsion to possess a non-urban single-family house that is engraved in the minds of the Flemish people.”

Omnipresent

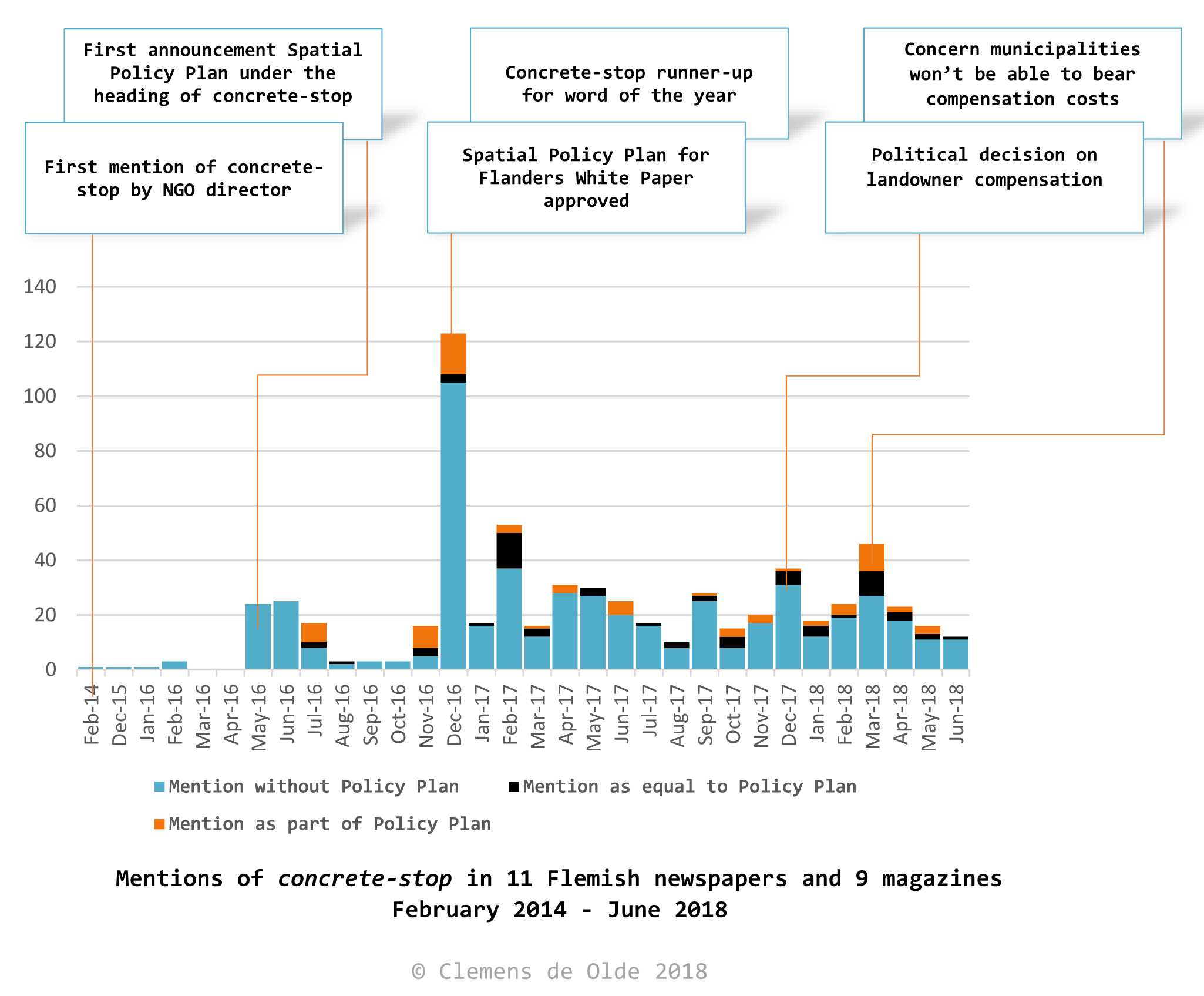

The term concrete stop does not appear in the Green of White Papers for the Spatial Policy Plan, yet the term is omnipresent in Flemish media and its use far outstrips that of the plan’s official title. In order to understand the career of the concept I performed a media analysis where I charted all articles that mention the terms concrete-stop and Spatial Policy Plan. The results are shown in the graph below.

Prior to February 2014 the term did not exist in public debate. It was then introduced in three subsequent articles by the director of an environmental NGO, but not connected to specific spatial policy. The first wave of articles broke in May 2016 when newspaper De Morgen got an exclusive look at the preliminary documents for the new policy plan and headlined their report “Schauvliege wants BETONSTOP” (Joke Schauvliege is Minister of Environment). This launched the term connected to the Spatial Policy Plan into the public debate. From then on it keeps appearing in news reports on the plan-in-preparation with an explosion in December 2016 when the Flemish Government approves the White Paper. That same month concrete-stop is nominated in the annual election for word of the year and ends as runner-up. Subsequent waves can be traced to developments in the dossier. From February 2014 until July 1st 2018 the term is found in 658 articles.

From the White Paper’s approval the term starts to appear in a majority of cases even without mention of the policy plan. The results show that “concrete-stop” is starting to lead a life of its own, becoming a force in its own right, without proper contextualization as part of a 200-page strategic spatial policy document. What’s more, in some ten percent of cases the term is explicitly equalized to the Spatial Policy Plan through formulations such as:

‘It is just another indication that the Spatial Policy Plan Flanders, popularly called 'concrete-stop', requires a cultural change’ (De Standaard 8-2-17).

Controversial

So what does the metaphor do? Unlike the ones mentioned above, concrete-stop wasn’t conceived by planners. Despite the first mentions by an NGO director, the journalist of the May 2016 article when asked, stated that he came up with the term himself in an attempt to make a terrible policy term such as the Spatial Policy Plan for Flanders more accessible to the reader. This is ironic because even though the media declares the concrete-stop to be very controversial, it has created and disseminated the term itself. There is actually extremely little mention of citizens’ voices in the press coverage on the new Spatial Policy Plan.

But controversial it is. The metaphor of concrete-stop might be understood to strike at the heart of the Flemish planning culture and the importance of the self-built single-family home therein. It is an image that engenders fear of losing value of land acquired long ago and the opportunity to build there for one’s (grand)children or to sell it to supplement one’s pension. Additionally it engenders images where residential choice might not be as free as it once was. Indeed, when posed as a side question in a series of interviews on residential satisfaction (De Olde et al., 2018), respondents stressed the importance of the freedom of choice of where to live and did not think that this choice could be lawfully restricted by a concrete-stop. Not being able to build anymore can be understood as a threatening to the large numbers that subscribe to this housing-economic model, which makes the Spatial Policy Plan framed as concrete-stop a very sensitive issue.

Concrete-stop seems to have been an excellent choice of metaphor then to stir up quite a bit of public unrest. The choice of metaphor affects the contents of the policy plan, much to the chagrin of the politicians responsible. Both the Minister of Environment and the Flemish Prime Minister now push back on the term. The latter states in a newspaper interview:

‘That’s why I’m so annoyed by the term concrete-stop, because that’s not what it is about. I don’t even know where that word came from so suddenly.’ (Het Nieuwsblad, 3-12-2016)

While experts and an increasing amount of politicians agree that it’s high time to reduce the spatial uptake in Flanders, the introduction of the term concrete-stop seems not to have helped to promote public support for the new Spatial Policy Plan. It is still uncertain whether the plan will be approved before the elections of next Spring but if it does, it will almost certainly be in the next few weeks before political summer recess. Should that happen then it won’t be a surprise when the headlines read: CONCRETE-STOP APPROVED!

Postscript

Friday July 20, the Flemish Government approved the new Spatial Policy Plan as part of a larger package of decisions made before summer recess. Interestingly enough, the main newspapers paid little attention to the concrete stop the following Monday. New regulations regarding energy policy waste management were at the center of the media’s attention. Perhaps the potential for a media outcry has exhausted itself now that the plan has been approved, perhaps other decisions present a more immediate influence on citizens’ daily lives. Nonetheless when it was mentioned, the entire spatial policy plan was subsumed under the heading of concrete block. Whether this bodes well as indicator for the effectiveness of the new policy plan remains to be seen.

This article is part of a feature anticipating the replacement of the planning system in Belgian region of Flanders in 2019.

Biography

Clemens de Olde studied sociology and philosophy at the University of Amsterdam where he developed an interest in cities and space. Currently he is PhD researcher in sociology at the University of Antwerp. His PhD research focuses on urbanization and the transformation of Flemish and Dutch planning culture.

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.

Comments 1

[…] Brons wrote about inclusive sustainable diets as a means of supporting and celebrating ethnic diversity. Her research shows that the inherent […]