Between Earthquakes and Urban Dreams: Planning Realities in Istanbul

Author: Başak Suvakçı

I. Living on the Fault Line

Turkey has always lived alongside earthquakes. Since 1999, the country has endured five major tremors exceeding magnitude 7.0, according to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS): the İzmit and Düzce earthquakes of 1999 (Mw 7.6 / 7.2), the Van earthquake of 2011 (Mw 7.1), the İzmir earthquake of 2020 (Mw 7.0), and, most recently, the devastating Kahramanmaraş earthquake of 2023 (Mw 7.8) (United States Geological Survey, 1999a, 1999b, 2011, 2020, 2023).

Istanbul, one of the world's fastest-growing metropolitan regions, stands at the crossroads of continents and cultures. Despite the capital's relocation to Ankara in 1923, the city has remained Turkey's beating heart: its industrial, commercial, and intellectual powerhouse (Paköz et al., 2019). Strategically positioned between Asia, Africa, and Europe, Istanbul is within a three-hour flight of 1.5 billion people. With Turkish Airlines now reaching more than 350 destinations worldwide, the city has become one of the most connected places on the planet. Economically and culturally, Istanbul leads the country, generating nearly half of all tax revenues and more than half of its economic output, drawing millions of visitors each year, and thriving as a vibrant mosaic of ethnicities, religions, and migrant communities (Paköz et al., 2019).

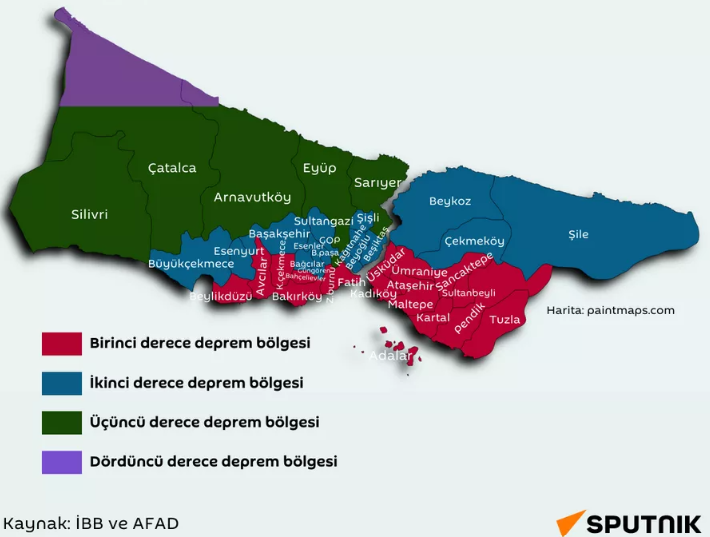

However, this very centrality makes Istanbul the country's most vulnerable point of concern. Scientists warn that the city is likely to experience another major earthquake of magnitude Mw 7 or greater, the first since 1766 (Gürkan, 2023). Prof. Naci Görür further cautions that around 2.5 million residents could be at risk of death in such an event, which he estimates could reach a magnitude between Mw 7.2 and 7.6 (Duvar English, 2023). From the tremors of the eighteenth century to the devastation of 1999, Istanbul has rebuilt itself time and again. Yet today, the question is no longer if the city will shake, but whether we are truly ready when it does.

After 1999, new laws were passed and hopeful promises made. Two decades later, those promises still resonate: are we rebuilding for safety or for profit? Urban regeneration has defined Türkiye's planning agenda for the past two decades (Sakarya et al., 2025). The 1999 Marmara Earthquake, which claimed over 18,000 lives, revealed the fragility of the country's cities. The 2011 Van Earthquake deepened that awareness, leading to the 2012 Disaster Law (No. 6306), which identified "at-risk" buildings and zones to make urban spaces safer. Yet, the 2023 Kahramanmaraş Earthquake brought the same urgent question back into sharp focus.

When guided by science and genuine public participation, urban regeneration can do more than modernize; it can help cities survive. Still, Istanbul's readiness remains uncertain. The city needs more than a million new homes (KONUTDER, 2025), yet much of today's construction still prioritizes profit over protection. Thus, the question lingers: are we preparing for the next earthquake or merely rebuilding for the market?

II. Urban Policies and the Politics of Transformation

Since the 1950s, Istanbul and other major Turkish cities have grown into earthquake-prone areas, resulting in a dense, fragile building stock (Balaban, 2019). The Ministry of Environment and Urbanisation estimates that about 600,000 homes in Istanbul are at risk of demolition and reconstruction over the next 15 years (Habertürk, 2017). The city's population has jumped from 691,000 in 1927 to over 16 million today (Erbay, 2023; Mazman, 2020; World Population Review, 2025), fueling this growth and putting pressure on construction, which highlights the conflict between economic goals and safety.

Alkışener et al. (2009) explain that urban transformation in developing countries is different from the Western model. Industrialized countries completed modernization by the 19th century, but Türkiye's urbanization accelerated only in the mid-20th century, leaving its cities caught between industrialization and globalization. Today, digital networks and global capital have blurred the line between rural and urban life, making connectivity the main force for change.

Effective transformation, they argue, must balance three dimensions:

- Social: education, social infrastructure, and community life;

- Economic: diversified industries and new employment;

- Physical: rehabilitated housing, cultural and green spaces, and safety.

III. 1999: When Istanbul Awoke

The 1999 Marmara Earthquake was a turning point. The first big regeneration project started in Zeytinburnu, a district known for irregular housing and poor infrastructure. The Zeytinburnu Urban Transformation Atelier of the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality led the project, aiming to create safe corridors, gathering spaces, and green belts for emergencies (Dülgeroğlu Yüksel, 2023). This project became the model for wider post-disaster planning in Istanbul.

The 2012 Disaster Law built on this model and set new safety standards. However, Yüksel (2023) and Torus & Aydın Yönet (2016) note that it often led to luxury redevelopment rather than strengthening existing areas. Kuyucu and Ünsal (2010) stress the need for fair and careful approaches, especially where informal housing is close to historic neighbourhoods.

In short, after 1999, Istanbul's regeneration often focused more on looks and investment returns than on lasting safety. To build real urban resilience, everyone involved -residents, experts, and government- needs to work together openly, transparently, and with a focus on community needs.

IV. After Hatay: The Same Mistakes Again?

The 2023 Kahramanmaraş (Hatay) Earthquake brought Türkiye's ongoing earthquake risks back to the forefront. Like the 2011 Van Earthquake, it brought back worries about what would happen if a similar disaster struck Istanbul. The media quickly focused on the city's high-risk areas, questioning if Istanbul is any better prepared than it was twenty years ago.

Earlier, the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality, in collaboration with Middle East Technical University, produced the Earthquake Master Plan for Istanbul (EMPI)—a comprehensive framework advocating the demolition of unsafe structures, retrofitting high-risk areas, improving governance, and preserving natural and cultural heritage (Erdik & Durukal, 2017). Yet, as Sakarya et al. (2025) observe, the Hatay disaster revealed deep inconsistencies between legislation and implementation. Some regenerated districts performed well, suffering minimal damage, while many officially "at-risk" areas remained untouched or were misclassified altogether. The episode underscored weak scientific risk assessment and how economic and bureaucratic priorities continue to outweigh resilience. In effect, urban transformation still tends to favour development over safety.

So, what has Istanbul really gained? Better building codes? More awareness? Perhaps. But the bigger question is whether people are actually safer or if the skyline just looks newer. Real resilience is built not only with concrete and steel, but with trust, fairness, and collective effort.

Türkiye's regeneration policies still confuse growth with safety. Bureaucratic delays, legal disputes, and speculative projects slow genuine progress. To truly move forward, five things are essential: integrate legal and social frameworks, rely on solid data, involve communities, monitor results, and focus on resilience, not profit.

For centuries, Istanbul has lived between earthquakes and dreams of renewal. Each disaster sparks panic and debate, but real change fades too soon. Until safety matters more than speculation, Istanbul will keep rebuilding the same story: a city waiting, not preparing…

References

- Alkışer, Y., Dülgeroğlu-Yüksel, Y., & Pulat-Gökmen, G. (2009). An evaluation of urban transformation projects. International Journal of Architectural Research (Archnet-IJAR, 3(1), 17–29. https://doi.org/10.26687/archnet-ijar.v3i1.251

- Balaban, O. (2019). Urban transformation and disaster risk: A case of Istanbul. Journal of Urban Studies, 56(4), 512–526.

- Dergipark. (2023). Urban transformation policies in Türkiye. https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/article-file/3207243

- Duvar English. (2023, August 6). 2.5 million people will face danger of death in expected major Istanbul quake, veteran seismologist warns. https://www.duvarenglish.com/25-million-people-will-face-danger-of-death-in-expected-major-istanbul-quake-veteran-seismologist-warns-news-62848

- Dülgeroğlu Yüksel, Y. (2023). Some thoughts on urban renewal and natural disasters. Journal of Technology in Architecture Design and Planning (JTADP, 1(2), 84–92. https://doi.org/10.26650/JTADP.23.001

- EMPA. (n.d.). Timber structures research group. https://www.empa.ch/web/s303/timber-structures

- Erdik, M., & Durukal, E. (2007). Earthquake risk and its mitigation in Istanbul. Natural Hazards, 44(2), 181–197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-007-9129-9

- Gürkan, K. (2023). A damage report document on the 1766 İstanbul earthquake. Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Cumhurbaşkanlığı Devlet Arşivleri Başkanlığı. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10466546

- IMARC. (2025). Turkey commercial real estate market size, share, trends and forecast by type, end use, and region, 2025–2033 (Report ID: SR112025A23703). Retrieved May 2025 from https://www.imarcgroup.com/turkey-commercial-real-estate-market

- KONUTDER. (2025). İstanbul'da gelecek 10 yılda konut ihtiyacının tespiti: Konut sektörüne yönelik değerlendirme ve öngörüler. Retrieved May 2025 from https://konutderpwcistanbul-konut-ihtiyaci-calismasi2202504vf3-1744989716961.pdf

- Kuyucu, T., & Ünsal, Ö. (2010). Urban transformation as state-led property transfer: An analysis of two cases of urban renewal in Istanbul. Urban Studies, 47(7), 1479–1499. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098009353629

- Mazman, Ö. A. (2019). The demography of Istanbul after the foundation of the Republic. History of Istanbul. Retrieved May 2025 from https://istanbultarihi.ist/464-the-demography-of-istanbul-after-the-foundation-of-the-republic

- Sakarya, A., & Bektaş, Y. (2025). Urban regeneration in response to natural disasters: Insights from the 2023 Kahramanmaraş earthquakes. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 40, 1541–1571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-025-10213-1

- Süzer, Ö. (2021). LEED-certified mixed-use residential buildings in Istanbul: A study on category-based performances. ITU A|Z, 18(1), 139–152.

- Torus, B., & Yönet, N. A. (2016). Urban transformation in Istanbul. In Archi-Cultural Interactions through the Silk Road: 4th International Conference Proceedings (pp. 1–8). Mukogawa Women's University, Nishinomiya, Japan.

- United States Geological Survey. (1999a, August 17). M 7.6 – 4 km ESE of Derince, Turkey [Event summary]. U.S. Geological Survey. https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/usp0009d4z

- United States Geological Survey. (1999b, November 12). M 7.2 – 8 km S of Düzce, Turkey [Event summary]. U.S. Geological Survey. https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eventpage/usp0009hev

- United States Geological Survey. (2011, October 23). The 2011 Mw 7.1 Van (Eastern Turkey) earthquake [Report]. U.S. Geological Survey. https://www.usgs.gov/publications/2011-mw-71-van-eastern-turkey-earthquake

- United States Geological Survey. (2020, October 30). Magnitude 7 earthquake off the coast of Greece and Turkey [News release]. U.S. Geological Survey. https://www.usgs.gov/news/featured-story/magnitude-7-earthquake-coast-greece-and-turkey

- United States Geological Survey. (2023, February 6). M 7.8 and M 7.5 Kahramanmaraş earthquake sequence near Nurdağı, Turkey (Türkiye) [News release]. U.S. Geological Survey. https://www.usgs.gov/news/featured-story/m78-and-m75-kahramanmaras-earthquake-sequence-near-nurdagi-turkey-turkiye

- Wang, Q.-C., Sun, M., Liu, X., Tao, F., Yang, D., & Bardhan, R. (2023). Reflecting city digital twins (CDTs) for sustainable urban development: Roles, challenges and directions. Sustainable Cities and Society, 91, 104444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2023.104444

- World Population Review. (2025). Istanbul population data. Retrieved May 2025 from https://worldpopulationreview.com/cities/turkey/istanbul

Author

Başak Suvakçı

Regional Ambassador to Southeastern Europe (Turkey)

Başak Suvakçı is an architect, lecturer, and researcher based in Istanbul. She holds a Master of Science in Architecture from Politecnico di Milano and currently teaches architectural structure design at Yeditepe University. Her academic work focuses on adaptive reuse, sustainable construction, and circular material strategies, and explores the intersection of architecture, artificial intelligence, and deep learning.

Fluent in English, Turkish, and Italian, Başak builds bridges between academic and professional communities in Türkiye and Europe, maintaining active collaborations with architectural networks in Italy. Her current research investigates how AI and computational design can enhance architectural and urban analysis by linking data-driven modeling, material innovation, and design optimization.

As Regional Ambassador to Southeastern Europe for AESOP Young Academics, she is dedicated to fostering inclusive and critical discussions on planning and design, amplifying the visibility of emerging scholars, and connecting Türkiye's academic community to global research platforms through collaboration and digital engagement.

https://www.linkedin.com/in/basaksuvakci/

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.

Comments